10 year deadline

Earth orbit assembly?

Rocket size of a battleship?

Enter midlevel tech taking career risk

A govt memo 9 pages long, single-spaced

"somewhat as a voice in the wilderness"

2 small ships in lunar orbit

Idea from 1916

Apollo 8

A Storyteller Sent Man To The Moon

You can go as far back as cave paintings, or go as cutting edge as the ocean of content available on every social network or mobile-messaging platform, to realize one thing.

We can’t help ourselves when it comes to storytelling. We won’t shut up. We just can’t stop. And thank goodness for it.

There are so many reasons for our stories. Some are shared and forgotten about.

Some are passed down from parent to child for generations. They have been recited/sung around a fire, chanted in temples, etched in stone, pressed into clay, painted on vellum, written on parchment, pressed on paper or recorded in digital media. The best stories come with a lasting impact. They alter the ebb and flow of humanity’s norms and suddenly a routine incoming tide becomes a tsunami.

The landscape of the world’s truths is redrawn.

Apollo 8 launched on December 21, 1968.

This was the first human crewed mission with the Saturn V rocket — this was the rocket NASA was betting on to take man to the moon, and it paid off:

“Apollo 8 took three days to travel to the Moon.

It orbited ten times over the course of 20 hours, during which the crew made a Christmas Eve television broadcast where they read the first 10 verses from the Book of Genesis. At the time, the broadcast was the most watched TV program ever. Apollo 8’s successful mission paved the way for Apollo 11 to fulfill U.S. President John F. Kennedy‘s goal of landing a man on the Moon before the end of the 1960s. The Apollo 8 astronauts returned to Earth on December 27, 1968, when their spacecraft splashed down in the Northern Pacific Ocean.

The crew was named Time magazine‘s “Men of the Year” for 1968 upon their return.”

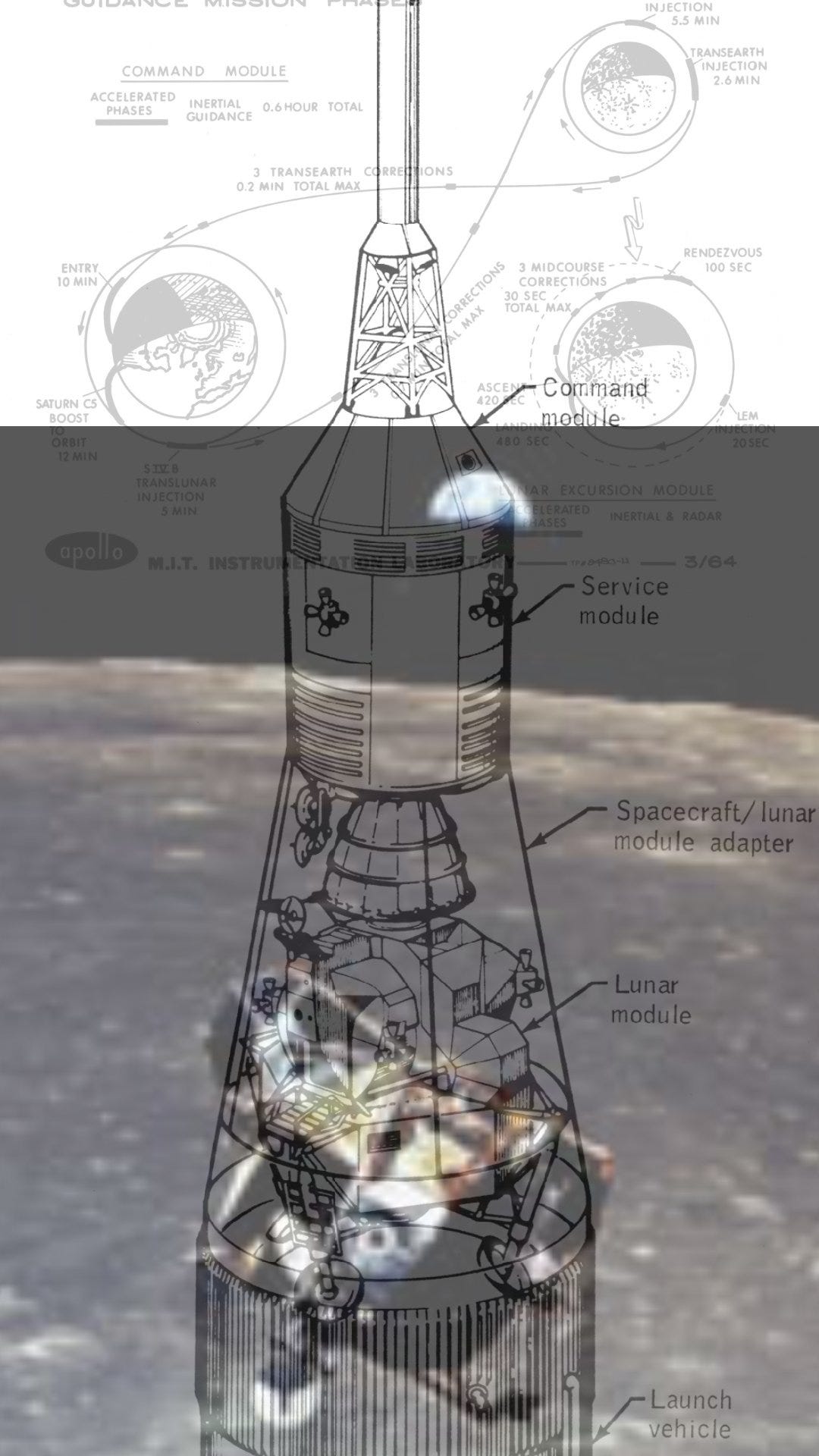

The Apollo 8 mission was like a big pass-fail test of the Saturn V and the Command Module (the capsule that the Apollo astronauts would use in a return splashdown back to Earth) BUT one crucial element was NOT yet tested. The Apollo Lunar Lander. Below is the moment with the actual spacecraft used by Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to land on the moon, on July 20, 1969, for the Apollo 11 mission.

And it almost didn’t happen.

Apollo was conceived near the end of the Eisenhower presidential administration and when President Kennedy made his famous speech about sending a man to the moon by the end of the 1960s, the US had only one manned mission completed, which had lasted all of a few minutes. Nobody had figured out yet how this was going to be done.

One guy had a story to tell about how to do it and his name was John C Houbolt.

We know the names of the astronauts (sometimes) and JFK’s speech about getting to the moon but there was one guy who really helped make that happen. Houbolt shared a story that helped NASA send man to the moon.

At the beginning of the push to go to the moon, some in charge wanted to send a big rocket to the moon and back but it would require a huge rocket with a lot of fuel, a/k/a “direct ascent”, and one proposed rocket, called “Nova”, would be as big as a battleship. Big, heavy, risky and very expensive.

There was another idea called Earth Orbit Rendezvous but that was also expensive and risky. Everything had to be assembled in Earth orbit and it still required a relatively big rocket to go the Moon. (Above image credit, of the Direct Ascent Scenario, from “The Virginian Pilot“)

Houbolt, a mid-level engineer, was about to elbow his way into a conversation between political giants about how to make JFK’s goal possible with a less expensive idea but it was controversial. He drew upon an idea that was suggested as far back as 1916 (!), “Lunar Orbital Rendezvous” or “LOR”.

“LOR” was a two-part plan. It used two spacecraft — which included a ship that would orbit the moon, the “Command Module” (that was everyone’s ride back home to Earth) and another ship that actually landed on the moon, the “Lunar Excursion Module”, the “LEM”. After the astronauts were done exploring the Moon, they would use the LEM (or the top part of it actually) to take off from the Moon, and dock with the Command Module that was orbiting the Moon. With everyone in the Command Module, the LEM was left behind and the astronauts headed home for a splashdown reentry.

Houbolt was possessed by his narrative, but many superiors were strongly opposed and it was ugly for him. But he talked, and kept talking about it. He would not shut up. He wrote a memo. Nine pages long. Single spaced. It began with what was a pretty unusual sentence for a government memo in the 1960s:

“Somewhat as a voice in the wilderness, I would like to pass on a few thoughts on matters that have been of deep concern to me.”

Quite an opening line. But it turned out that Houbolt was right:

“While some aspects of Houbolt’s initial estimates were off (such as a 10,000 pound Apollo Lunar Module which was ultimately 32,399 lb (14,696 kg)), his LOR package proved to be feasible with a single Saturn V rocket whereas other modes would have required two or more such rocket launches (or larger rockets than were then available) to lift enough mass into space to complete the mission.”

A voice in the wilderness told a story that helped us reach past moonlight and touch the moon.

(*It would turn out to be a blessing in disguise for one mission, Apollo 13.)