Breach The Sky To Brave The Stars

Dreams As The Stars Of Our Imagination, Guide Us To The Future

Welcome to an essay “From The Future”, the final in a summer series of thoughts about “The Future”. After this, the next pieces will be fiction for my novels for a few weeks. Future + Fiction is the formula for everything, whether it’s an essay, story or chapter.

This is a riff about how stories of “the future” merge into history.

Soon after the beginning of the 21st century, more people began to live in urban than rural areas. Today, over half of the world’s population, 55 percent, lives in towns and cities, with urbanization projected to reach almost 70% by 2050. The lights of the night sky have been washed out by the lights of Man’s world.

For centuries, we navigated by starlight suspended in the dome of eternity, now we make our way by the invisible lights of satellites, an ancient dream of flight made real.

There are other lights, however, which guide humanity at night, or during sleep. In our minds are unique constellations, collections of stories, made of imagination. This is where we rewrite the world inside us after sunset. Most of it is forgotten by sunrise. Some, however, remember enough to rewrite the waking world.

Our imagination is where the impossible becomes possible, and the could-and-should-be is conjured in dreams. If freed through a special window, dreams can become the next, taken-for-granted, reality. This is where the future begins.

This is also the future at its most vulnerable, when released into the wilds of the real. Under the blistering heat of “the way things are” because “it is what it is”, of complacency and incumbency, most dreams are faded away and lose their light.

To see lights of the night sky again, we either retreat to the deep dark places, or advance beyond the veil of air wrapped around the world. We face the same choice with our dreams. My choice: We breach the sky to brave the stars.

But first we do battle with our eternal curse of doubt, as in self-doubt.

We judge ourselves with the sharp ends of long-tail distributions of our self-image.

We may Dunning-Kruger ourselves in-over-our-heads but worse, we undershoot too.

When we exert our self-image against the unrelenting gravity of limiting beliefs about everything, ourselves and the world, we suffer breaks and enjoy breakthroughs, and after brief pain, we recover stronger. We make things happen.

Other voices resound with, Ack-tually… BUT But but… Never before… impossible… wrong! The voices of inner (and outer) critics may resonate, but a lone voice calls to adventure. We each have the one voice that goes “What if? Why not”? Some listen.

We hear, feel, see, and know when someone listens to themselves, and “goes for it”.

Every advance of humanity began with someone hearing the call of “Why not”?

Every dream we take for granted as a part of history began with “What if?”

Compare the world today with the world fifty, a hundred, years ago, to see if become it.

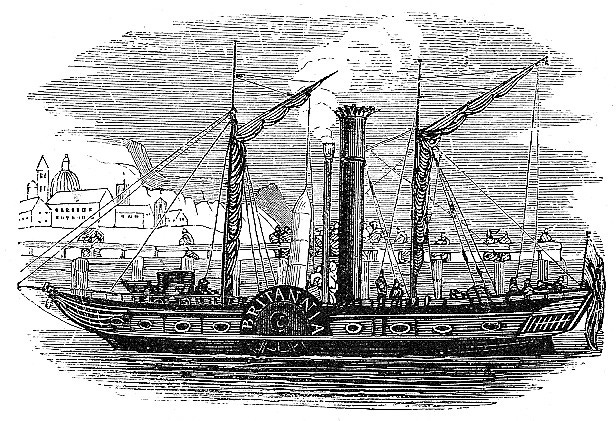

If “it” feels unnatural, this expanding envelope of what the world is like, you’re not alone. Someone who was not a fan of the Industrial Revolution still wrote,

“In spite of all that beauty may disown

In your harsh features, Nature doth embrace

Her lawful offspring in Man’s art; and Time,

Pleased with your triumphs o’er his brother Space,

Accepts from your bold hands the proffered crown

Of hope, and smiles on you with cheer sublime.”

-William Wordsworth, “Steamboats, Viaducts, and Railways” (1833)

It’s a scary thing, the future but it’s a part of who we are, our nature, to ask “what if”?

You’re reading these words because of a long chain of changes in the world, which were each strange, frightening, and bewildering at the time. The changes were realized by a long chain of people who remembered their dreams, listened to their brave voice, and found an opening through the right window.

EACH NEW REALITY IS OUTSIDE A SPECIAL WINDOW

Remember what I mentioned earlier: If freed through a special window, dreams can become the next, taken-for-granted, reality. This where the future begins.

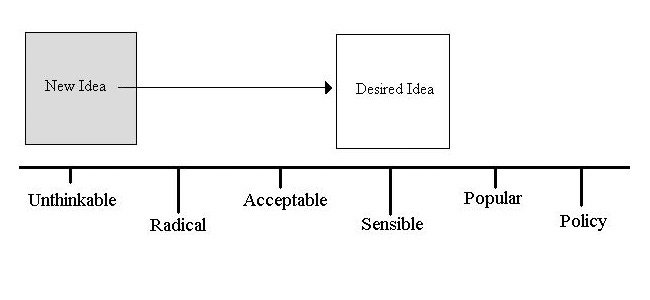

The “Overton Window”, from public policy analyst Joseph Overton, is defined as “the range of policies politically acceptable to the mainstream population at a given time”.

The idea of a “window” as a range is like a no-man’s zone filled with landmines. Stomp as heavy as you want on the safe spots of certainty, you live. Get brave, however, and maybe it all blows up, Boom! But, what if not all bravery is punished? What if a path is found to move forward?

There is another “window”, for a range of possibilities of the future.

If writing is motivated by writing for ourselves, then writing about the future is the sending of messages to our future selves. Most messages are a warning, Turn Back, There Be Dragons, Danger, You’ll Be Sorry, but a special few are an invitation, This Way Ahead, The World Is Not Flat, Man Can Fly, We Choose To Go.

The warnings are safe inside the range of the acceptable, where nothing changes. Here, we retreat to the deep dark places, under the light of a candle or a kerosene lamp, forgoing the electric light bulb, illuminated until the flame dies.

The invitations are “outside”, where the reward of the new tantalizes - no guarantees.

When our imagination exceeds others’ sight, they will treat us as blind to “the real world”, unrealistic, dangerous, a career or investment risk, a waste of time. Boom!

I think about what happened with Nikola Tesla, a genius who went through the window, again and again, and about how his days ended. If we want to bring tomorrow into today, do we take the risk to impoverish ourselves to enlarge, and enrich, the world? The most valuable ideas are shared, for a hoarded future is worthless.

"Special knowledge can be a terrible disadvantage if it leads you too far along a path you cannot explain anymore."

-Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson, “House Harkonnen”

How far do we dare create something so new as to be strange but could become accepted and ordinary, where a quest for the future leads to a new quotidian reality?

Christopher Vogler understood that films, as stories, work this way, as a mix of what is known and yet to be known, and wrote a famous memo for the film industry, based on the ideas of Joseph Campbell. In a later book which expanded on this, he said,

"artists who operate on the principle of rejecting all form are themselves dependent on form. The freshness and excitement of their work comes from its contrast to the pervasiveness of formulas and patterns in the culture. However, these artists run the risk of reaching a limited audience because most people can't relate to totally unconventional art… A certain amount of form is necessary to reach a wide audience. People expect it and enjoy it, so long as its varied by some innovative combination or arrangement and doesn't fall into a completely predictable formula."

— Christopher Vogler, “The Writer's Journey”, 3d edition)

Vogler’s advice here: stories work if we recognize them as relatable stories.

The form, of a new story should be a mix of conventional, enough to relate to, and unconventional, enough to tantalize.

A warning: Familiar and conventional format stories at their most concentrated extreme is nostalgia. If we’re only looking back, we risk fading away the “new new things” because we love too well, and miss too much, familiar forms and faces, old haunts, and childhood places. The retreat to certainties, and the past, risks the future.

The natural brilliance of dreams of “the future”, are washed out by the saturated lighting of longing for the past, a kind of saudade, wistful for a mythological, apocryphal, never was but should have been, nostalgia set on a “replay” loop.

This is the real price of an endless stream of everyone else’s never-ending retrospective past-as-present: we lose a part of “living in the now”, our thinking, and by extension, imagination.

Nostalgia at its extreme is a turning away from our imagination, which calls us through our dreams with new stories.

Remember, however, there is a window for a range of possibilities of the future.

There is where dreams come into play, freed through that window through stories.

These hardiest of dreams are calls to adventure for the world.

And they use unfamiliar words, words from another time, for new stories.

The unconventional part of stories of next new things will need a new language.

Take a piece of tomorrow, and put them into stories with new ideas, forms, and words.

Robert Anton Wilson played with forms and neologisms, new words, to break free of the past, to remind us, "If we're seeing the world our ancestors put in our language, we're not seeing the world we're living in". New Words helps us see New Worlds.

For fiction writing about and from the future, I volunteer that stories that work will have a pareto-like “80/20” distribution, 80 “familiar” and 20 “new”, which over time shifts, and flips to 20/80, as the “new new things” becomes the old norm.

Time for some history, to see how it’s happened before.

AD MELIORA - TOWARDS BETTER THINGS

To push past the “window” of what is possible is a risk. After falling, we pick ourselves up, learn, grow, and build. We risk falling towards better.

And even if we do not fall, sometimes we forget, only to rediscover the future again.

The 1851 “Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations” held in Hyde Park, London was hosted in a futuristic structure of metal and glass, created by a gardener, Joseph Paxton. Its design and construction presaged and predicted the next century’s skyscrapers with their bones of metal, and curtains of non-loadbearing walls of glass. Its modular design, and component construction, technology hinted at the future.

The Great Exhibition was over a 100,000 exhibits displayed in a building that was 400 feet by 1,800 in size, made with 4,500 tons of iron and 300,000 panes of special glass. It was made possible thanks to the repeal of a glass tax but also the failures of enough iron bridges, broken by the stresses of the railroad boom, to call for a Royal Commission to investigate and improve bridges. Those earlier failures led to better.

Henry Cole of the Society of Arts was a fan of the future promised by the industrial revolution, and suggested an exhibition of arts and engineering. Prince Albert, husband of Queen Victoria, as chair of a Royal Commission, agreed to Hyde Park but the missing piece was the building. It wasn’t a smooth process, 245 proposals failed, and reasons for opposition included a fear of promoting foreign goods, various theoretical health hazards, and the chopping down of some elm trees.

Paxton submitted his proposal only two weeks before the deadline, thinking he had no chance, assuming more established experts had already won the project. Despite believing he had no chance, he was still excited enough to doodle a sketch while at a meeting, and brought them to engineers. Win or not, a dream took hold of his mind.

What saved the day was that the Illustrated London News jumped the gun and published Paxton’s design. That pushed the Commission to abandon an earlier official selection and choose Paxton’s proposal. The fact that Paxton’s design was simple, fast to build, and with reusable parts may have made the choice easy to make. It even included a section that would envelope the 90 foot elm trees that objectors worried would be cut down.

Despite the profitable results, expert critics of the era were not impressed despite its admirers, which included Queen Victoria, who visited dozens of times between May and October 1851. The building was such a success that there were new exhibits elsewhere inspired by what British magazine Punch called a “Crystal Palace”.

The Palace may not have been the first design chosen by the Royal Commission, it was the one that changed expectations of what was possible with metal and glass. It was a little ahead of its time. Great metal structures, with walls of glass hung like curtains, became the norm a century later.

By the 1950s, the International Style, where towers of steel skeletons and glass walls became a fashionable industrial norm, was a fitting successor to the Crystal Palace, remembered more for its cutting-edge vessel than its contents a century earlier.

About that time something was coming in a new field, information technology.

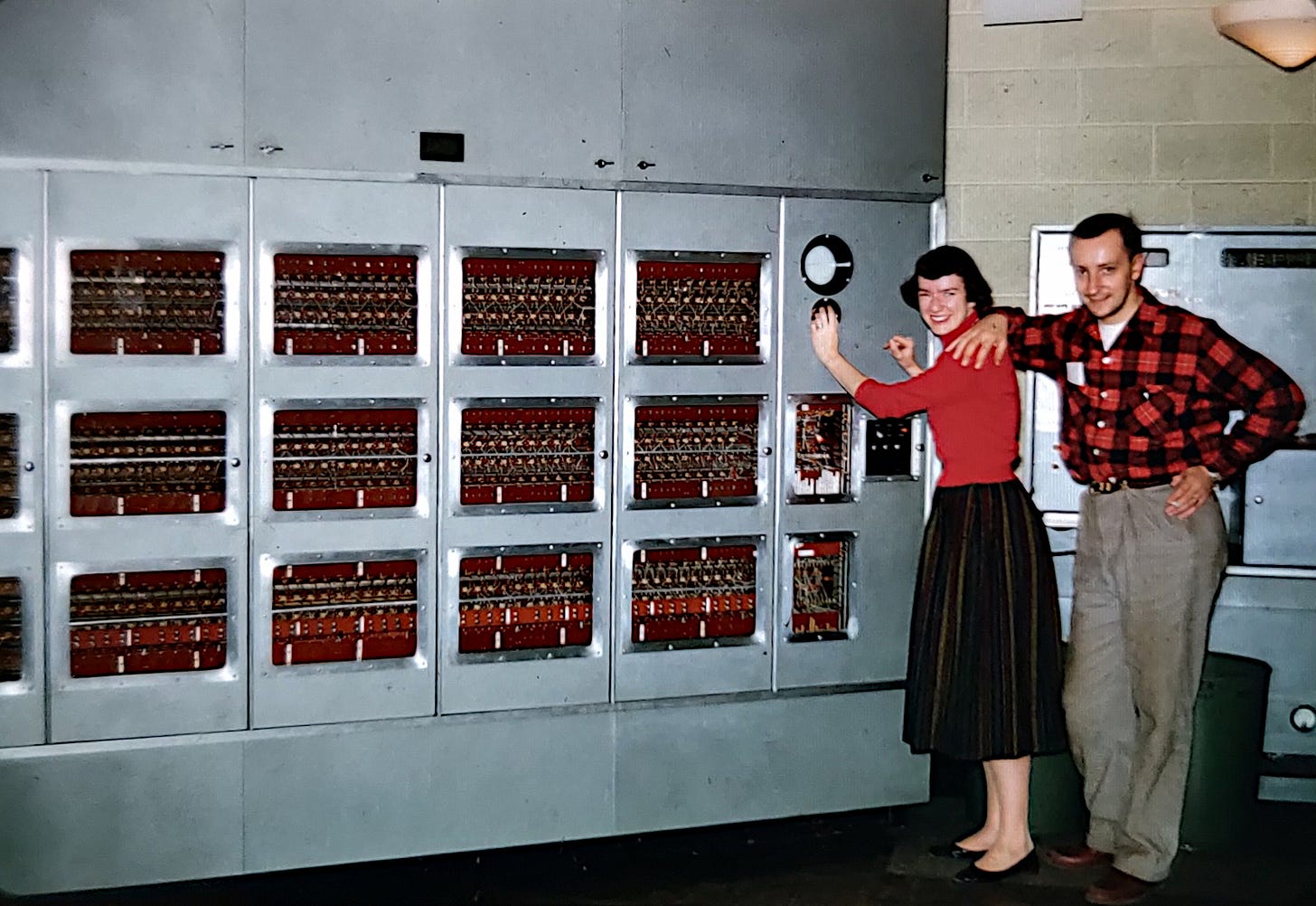

The first computer designed for and owned by an educational institution in the United States, the “Illiac I”, was built in 1952 for the University of Illinois. It also became the heart of new unintended community, an emerging virtual society.

That society was born in experiments in Computer Aided Instruction (“CAI”), for education, descended from behavioral scientist B.F. Skinner’s idea that technology should enable more individual instruction which is paced and matched to each student’s progress, with faster feedback loops, versus the single speed of classrooms.

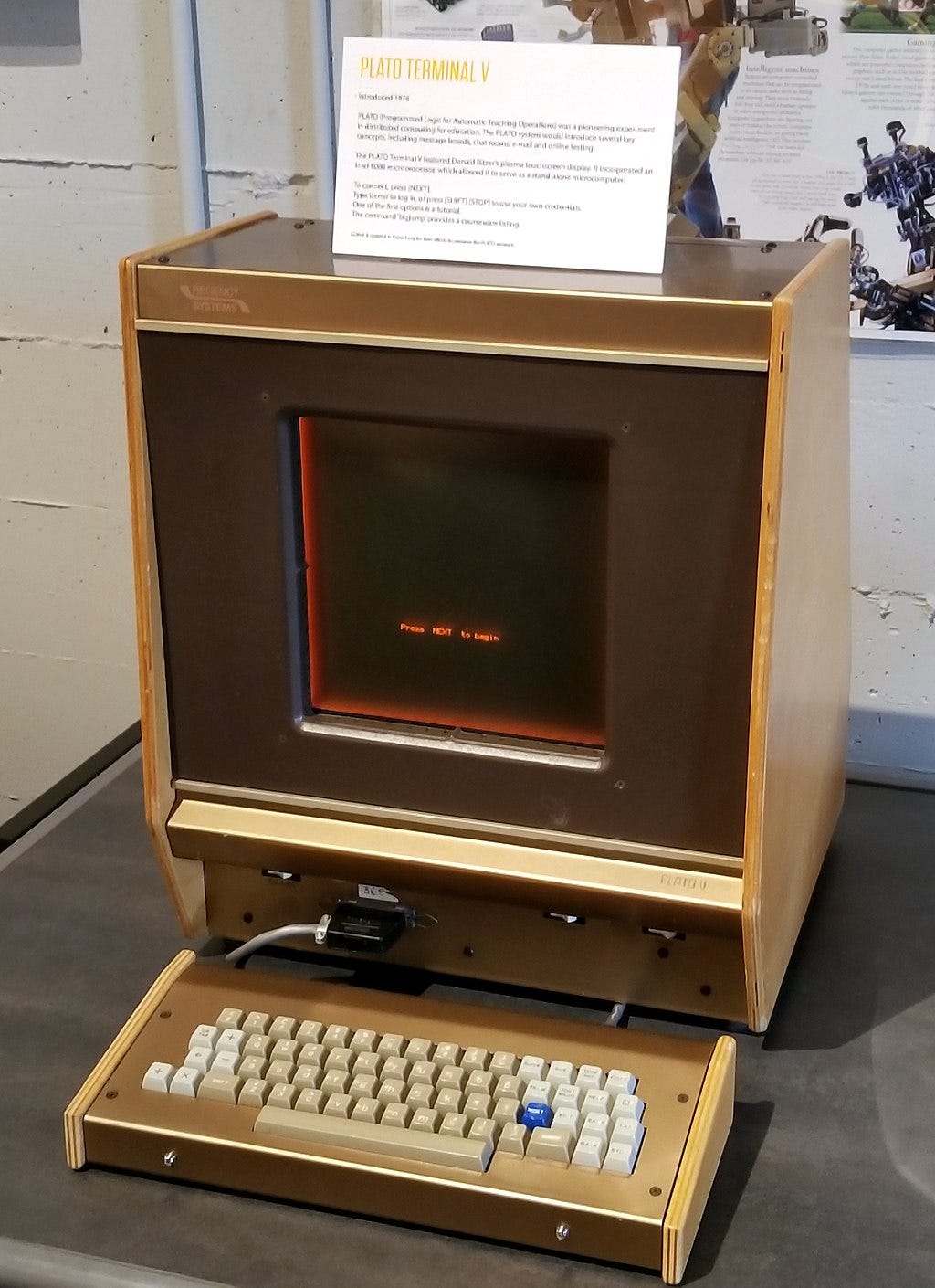

In 1960, “Project Plato” (“PLATO” stood for “Programmed Logic for Automatic Teaching Operations”), one of the longest running experiments and ventures in CAI education was founded by an University of Illinois engineering student, lab assistant Don Bitzer.

If this were a Vogler-framed story, then PLATO’s story has two parts. The conventional part of its story was its education mission. The unconventional new part was time-sharing of dedicated mainframes to power Skinner-style teaching machines.

PLATO’s ease of use was despite not running a proper programming language in the eyes of some critics. Over its time, hardware evolved from a television display and simple keyboard made for one user, and culminated with a network of thousands of plasma screens with a “warm orange glow” with multi-user features, touch screen capability, microfiche projection, and synthetic woodwind chimes. It won over a generation of young programmers and designers, including pre-teen high school students, unofficial beta testers who “broke” PLATO, forcing constant improvements.

The network inspired students, at local high schools around University of Illinois (UI) with a familiar fun spark, to create games built on an architecture intended for creating “lessons”, and went to the killer application of messaging between users.

Every familiar element of 21st century online society had a proto-version by the 1970s: email, education, multiplayer games, emojis, chat, forums, and even “catfishing”.

These demands will continue even as the times someday evolve into an age defined by whatever machine intelligence becomes, whether it’s labeled as “artificial intelligence” or becomes a stack resting on quantum computing.

Wherever the infrastructure is housed, in data centers in places like New York, or on vast tracts owned by the “Platform” companies, data farms, the landing points for our experiences will remain close to home, to humanity.

The last New World becomes the new Old World, with each change for how all the messages are written and delivered, even as the meaning within remains the same. It will always be “Hello, World”.

50 years before I wrote these thoughts, on a network which has a “Notes” feature, someone else was doing it for the first time too.

In August 1973, the failure of an earlier feature designed for note-taking but adapted for two-way texting, led to the creation of “NOTES”, where a user could enter a “basenote” and other could respond, up to a chain of back-and-forth up to 63 entries. This is a familiar feature in today’s social networks and messaging but this quick solution built by a 17 year old U. Illinois freshman took over PLATO by storm. The legendary social network of “the WELL” created in 1985 had its predecessor in PLATO’s NOTES which grew a global user base since 1973.

The PLATO project opened the window but it would be other experiments which made it in the wild which changed what was possible for the mainstream population. By the 1990s, the window moved on, and the great network was powered down.

During its existence, some were inspired enough by PLATO hardware to guestimate via “Moore’s Law”, which came out in 1965, a few years after PLATO’s launch, about the potential for “personal computer”. Xerox PARC scientist, Alan Kay, imagined a “Dynabook” with flat panel and integrated computing, which emerged in the 80s/90s.

It was Xerox PARC which opened the next window, with a competing philosophy based on distributed computing power at the desktop level for networked computers, as opposed to PLATO’s time-share model. But PLATO’s vision made itself felt in revealing what its users wanted. In 1972, Xerox PARC engineers visited, and several PLATO features, such as Insert Display/Show Display, Charset Editor, Term Talk, and Monitor Mode, found their way in Xerox, in features for graphics, doodling, chat, and screen-sharing. Emissaries between these 2 societies exchanged visits over the 70s/80s.

Even Xerox didn’t see the promised land, however, for that was up to others, including Steve Jobs in the 1980s after his famed visit to PARC, and Marc Andreesen in the 1990s at the NCSA, which led to “the Internet” as a mainstream reality.

There were new lights of new dreams, leading to windows to the next new thing.

A next new thing: to breach the sky and brave the stars for real.

55% of the world lives in world that blots out the stars, 55% of America thinks we’ll breach the sky and see the stars again in 50 years.

Closing thoughts:

We are principals, not products, of our environment.

The past might have led to us but we make the future. It begins with a story,

with new words for new worlds, through windows open to the wilds of the future.

Each new story of the future is a call to adventure for the world.

Answer the call.

“A man sets himself the task of portraying the world. Through the years he peoples a space with images of provinces, kingdoms, mountains, bays, ships, islands, fishes, rooms, instruments, stars, horses, and people. Shortly before his death, he discovers that that patient labyrinth of lines traces the image of his face.” —Jorge Luis Borges, “Dreamtigers”, Epilogue

Killer title. Great stuff, Edward. Thanks for answering the call.