Our Imagination Is A Camera Of The Mind

Our Imagination Is A Camera For Taking Portraits Of The Future

Welcome to an essay “From The Future”.

After this essay, I plan to share chapters for my novels as part of writing in public.

Future + Fiction, Story + History, is my formula for everything From The Future, whether it’s an essay, story or chapter.

These pieces are best read online, via the Substack’s App, when you have fifteen minutes.

“Industry at its best… is the intersection of science and art.” —Edwin H. Land

This is a meditation on Art and Science. This is a riff on the overlap between them.

Art connects us to worlds which may already exist. Our imagination wanders far enough to discover them. Our power of creation gives us new tools, or new uses for old ones, to explore.

Art captures and recreates moments when optical fantasy becomes physical reality.

History is filled with people who could bridge the creative, works of knowledge, with the imaginative, worlds of dreaming.

One of history’s leading dreamer-explorers, Edwin H. Land, was captivated since childhood by the mysteries of light. He understood the power of the image, and that a photograph was an artifact which was both outside, apart from the artist, sharing a point-of-view, and inside, a part of the artist’s inner vision.

The moment Land read Robert W. Wood’s Physical Optics, he began a mission to create a synthetic polarizer which could save lives from the glare of headlights from oncoming vehicles at night. After just one semester at Harvard in 1926, he took a temporary leave of absence to work, uninterrupted, on this self-appointed quest. He began with an intense focus to study the science of light, optical physics and chemistry. Land wanted to solve a near-century old scientific puzzle written in light. There already were light polarizers made from large single crystals but they were expensive and could not be mass produced. Others tried and failed, but Land did it.

While Land never achieved his original commercial application, of preventing glare of the headlights of millions of vehicles at night, he did find new uses and commercial success with sunglasses, camera filters, special desk lamps, and train and airplane windows. At the 1939 World’s Fair, Land showed off 3-D movies. A demonstration of overlaying two circular polarizer pieces, which blotted out all light where they overlapped, became the inspiration for the original logo of a company that would become Polaroid.

Solving a long standing science problem led to a new art of the future in photography. It was, to borrow Land’s words, “a miraculous experience” of traveling to a new country. Land and Polaroid changed the future with the arts of spontaneous reality.

Let’s take a few steps back in time first.

Before photography, our images were etched, sculpted, drawn, and painted.

The dance between imagination and creation is an eternal duel, where the imagination of images tests the limitations of the means of their creation.

There is a painting, entitled “Entombment”, credited to Michelangelo or one of his pupils. It looks incomplete. It is said that the artist ran out of either the paint color Ultramarine, (from the Latin for “from beyond the sea” made from semi-precious lapis lazuli stones from Afghanistan) or the money for a paint more expensive than gold leaf.

Over 250 years after Michelangelo’s passing, a synthetic Ultramarine was invented in 1826, a century after the first synthetic colors in the 1700s (the first of which, Prussian Blue, was both an accident and the opposite of what was hoped for, a new red). At the same time, the future pattern of art was weaved by the looms of the textile industry. Textile makers wanted new colors, and therefore needed new dyes.

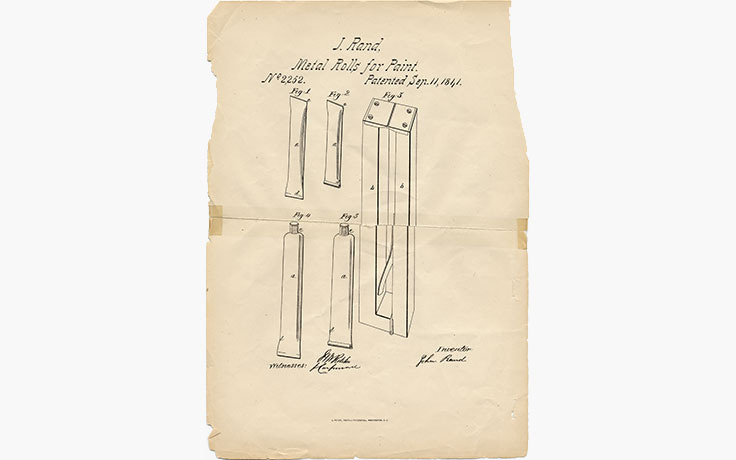

Meanwhile, in 1841, an American named John Rand made what seems a modest invention, collapsible paint tubes of pre-mixed paints. This meant painters could be outdoors or anywhere and experiment with painting, without the stress of mixing and handling paints. Some used stiffer horse-hair brushes to daub on the paint to capture a moment and its light at the same time they experienced it.

In that moment, seeds for the future of art were planted, for more spontaneous reality.

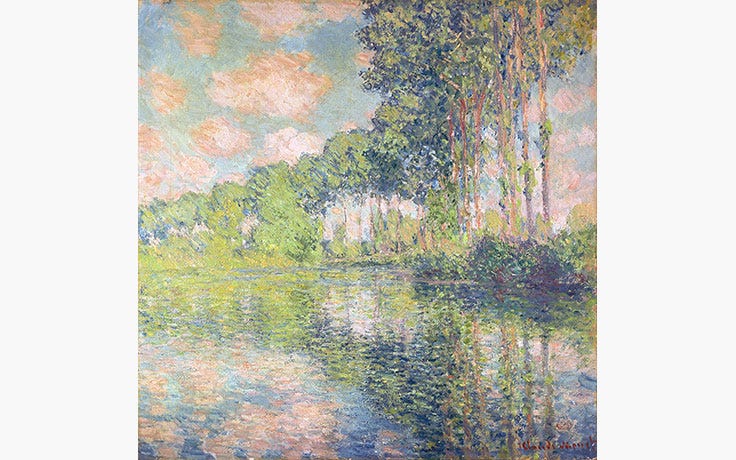

When I think of the great art of the 19th Century, I think of Renoir and Monet.

Today, their works are on the walls of the world’s galleries, museums, and in places of the wealthy. When pre-mixed paint in tubes which looked like toothpaste tubes, became commercially available by the 1860s, a rising cohort of artists, who were going for spontaneity in applying color to the canvas, embraced them. The Impressionists were accused by critics of the time as “dazzlers who painted only with intense colors”, and derided for techniques enabled by technology. It’s not the first time that new Art has been criticized for being ahead of its time, that it is accused of straying from “real art”.

Art’s ironic pragmatism is its potential to look to the creative potential of science, to borrow from and play with its advances, to fulfill the desires of imagination.

In fact, both Picasso and Pollack, among many artists, experimented with and explored for new colors and textures, like enamel paint and gloss enamel. Meanwhile new minds moved further ahead.

The electromechanical age gave way to the electromagnetic, and the first computer, ENIAC, intended for artillery calculations, was redirected for atomic weapons work.

It was only a matter of time before electromagnetism became the heart of the art of the future, since light is the most relatable aspect for every human who ever lived.

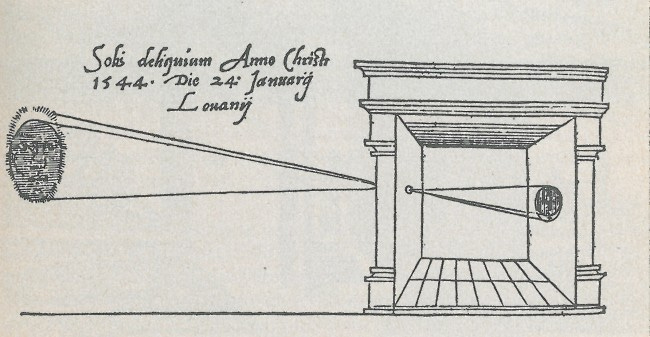

Centuries ago, we used the camera obscura to duplicate images. While the first credited term was recorded in 1604, mankind’s fascination goes back centuries, if not millennia according to some theories based on Neolithic-era evidence, and was worldwide.

It was Leonardo da Vinci, however, as part of his relentless interconnected curiosity, who connected the camera obscura to human eyesight in both art and science. Leonardo was fascinated by light, vision, perception, which informed his insight about perspective in his paintings, including The Last Supper. His unapologetic, and near transgressive, studies of cadavers led him to characterize the eye as a camera obscura.

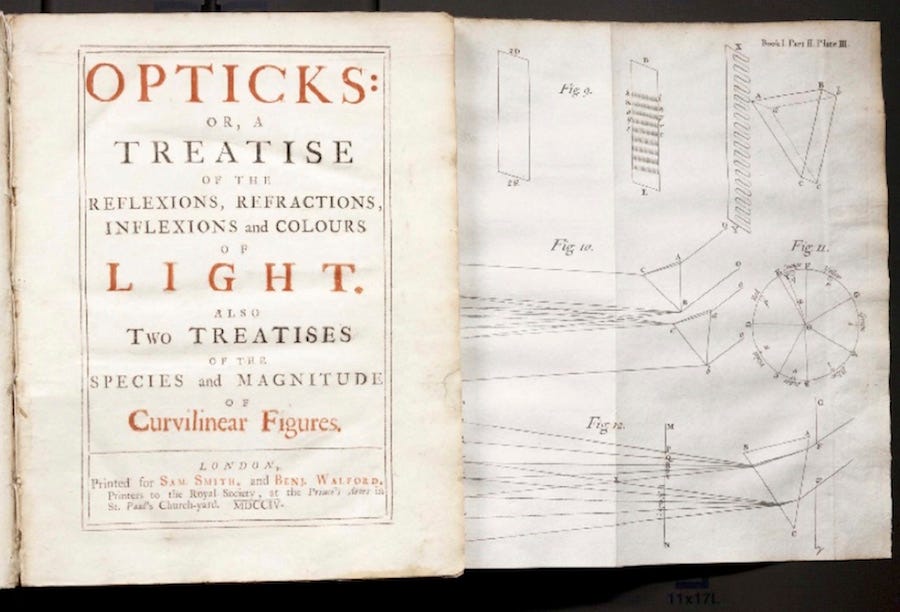

Later, Isaac Newton, after retreating home in 1665 from Cambridge, as the Great Plague ravaged London, occupied himself with a study of light. Like da Vinci before him, and Land after him, the future Sir Isaac was fascinated by the mystery of light, and discovered he could refract white light into different colors. He did it with a pinhole in a window shade, and a prism. With a second prism he recombined all the different colors back into white light.

Seven years later, he published a “New Theory of Light and Colors” with the “Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society”. Confined to this home, but freed by his imagination, Newton displaced 20 centuries of Aristotle’s model of light, as divine transmissions with roots in dark and light, with his compilation of everything he learned about light, in Opticks.

Some claimed that artists, including Johannes Vermeer, of using the camera obscura, and questioned their artistry, and imaginative and creative powers. It was as if all one had to do was trace an outline on paper and canvas cast by the light of such technology, and that because such art was so realistic, too perfect a creation of forced-perspective, that such art wasn’t legitimate. This is an age old never ending argument, about what is “real art”, which continues in the next use of light in art: photography.

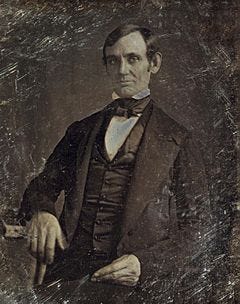

Not long before John Rand’s 1841 invention of prefab paint tubes was Louis Daguerre’s 1839 invention using silver plated copper sheets and silver iodide so that one could capture an image of a subject, usually a person sitting for a portrait. Daguerre, a romantic-style painter and print-maker, whose tableaus of illuminated paintings for his Diorama captivated Parisians, invented a tableau for light, inside a small box.

The light reflecting* off objects comes through an aperture, through a “hole” at the front of a box, a lens, and lands as a projection on a copper sheet held in the box.

*For the most part, object don’t “emit” light, they reflect light shone on them, unless you’re talking about sources of light, beginning with the sun.

Notwithstanding “mad hatters” in some instances, due to the dangerous chemicals involved, including mercury, cyanide and sulfuric acid, it marked a transition from art as solely the domain of reproduction by hand. This was the beginning of preserving the light of the moment and fixing it into place, thanks to chemistry.

What was not fixed into place, as always, was technology. In the 1880s, the new thing of photographic film had arrived, courtesy of George Eastman and Kodak. The era of celluloid for the still and moving image had arrived. This history is well known.

Time to jump forward in time to Edwin H. Land’s contribution to Art and Science.

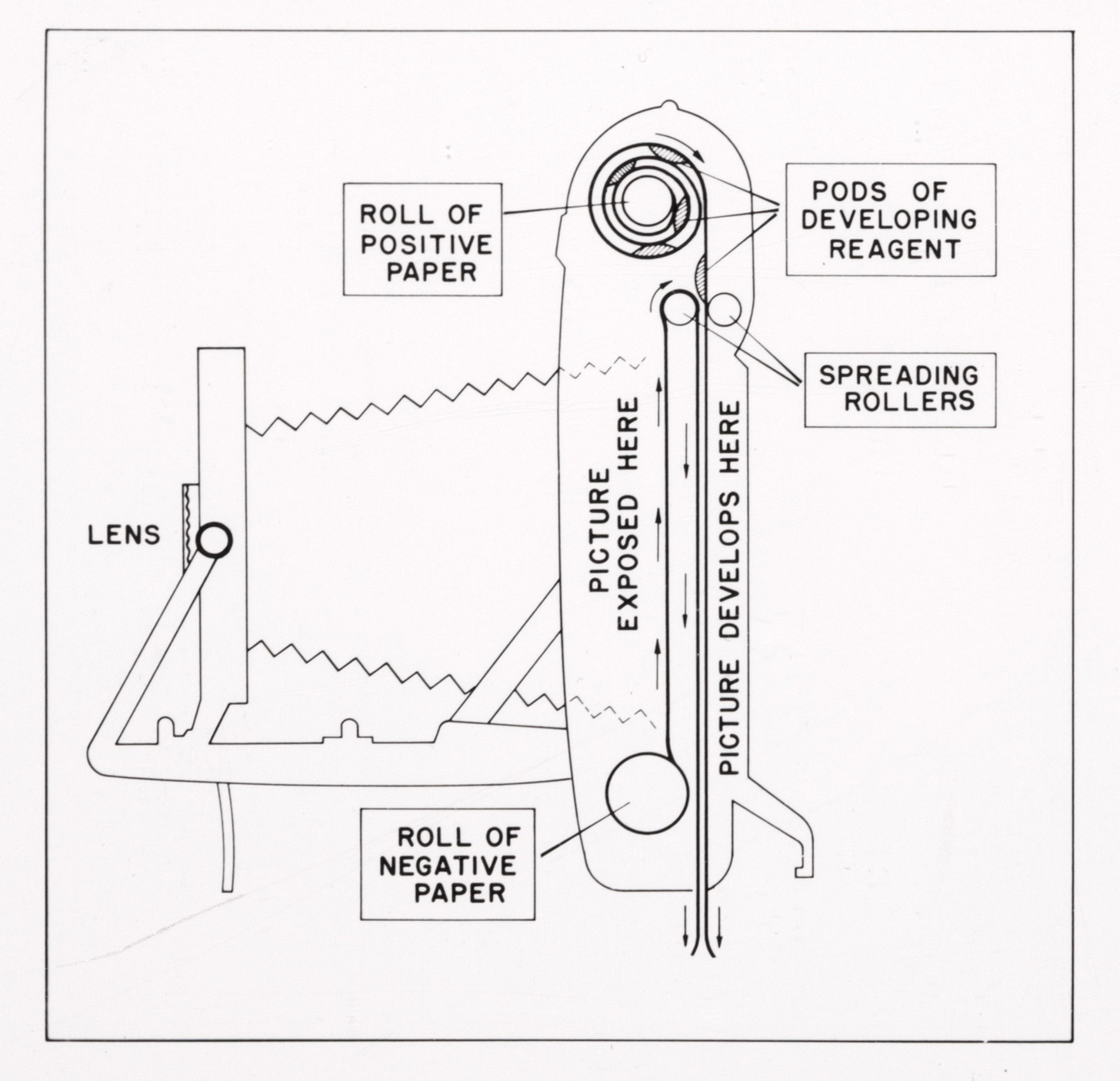

While the Second World War was still being fought, and after years of work and success, Land’s imagination took hold. On a 1943 vacation, his daughter Jennifer wondered why photos too so long to make. The usual process for almost a century required several steps, from photographer with a camera to film development in a darkroom. Inspired, Land wanted it to happen at the press of a button, in one device.

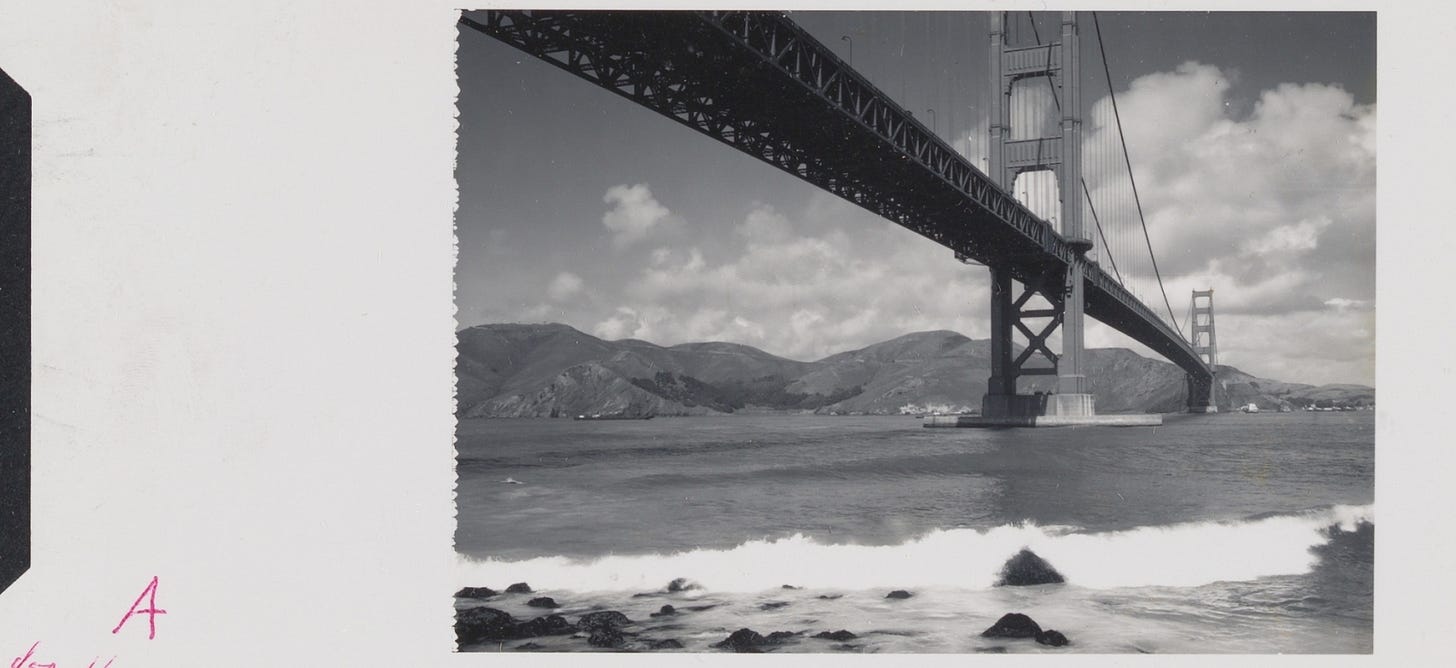

The birth of One Step Photography was the birth of a new artform, that could be created by anyone theoretically. A 1947 demonstration and debut of Polaroid’s new camera for the Optical Society Of America in NYC was the beginning of the kind of photography as most people today understand it: widespread, easy, and instant.

“By making it possible for the photographer to observe his work and his subject matter simultaneously, and by removing most of the manipulative barriers between the photographer and the photograph, it is hoped that many of the satisfactions of working in the early arts can be brought to a new group of photographers.” (“One Step Photography” by Edwin H. Land, 1949)

It was a futures bet, a bet the company move in a post-war America which meant less government /military spending. The successful debut at a Jordan Marsh department store meant the sale of all 56 “Model 95” cameras sold for $89.75 in 1948, or over $1,100 dollars for today’s equivalent price. The cutting edge device was even promoted with advertising on another new technology, television shows promo spots.

The new technology of instant photography captured the popular imagination because of its potential to inspire feelings through art everyone could make.

Land understood the implications and recruited Ansel Adams in the 1940s, knowing that his technology gave users “more of a chance to be an artist” (in the words of an article in U.S. Camera). To use a 21st century phrase, Land’s camera democratized photography, lowering the bar for creative expression, making it easier for people to experiment, and explore, to be an artist.

Thirty years later, in a chairman’s letter to the shareholders in Polaroid’s 1976 Annual Report, Land recounted that, “The magic of image making… almost merely layers of concepts… evoke in the observers of the image the whole spread of human emotions”.

The next change in instant photography was part of the rise of a multi-chromatic age.

After he solved the problem of how to achieve a near instant dry-photographic process, the long arc in Polaroid’s instant photography technology culminated in April 1972 with the “Special Experiment 70”, or “SX-70” camera. It was the triumphant milestone in a 30 year journey from 1940s sepia and monochrome to “Picture in a Minute” color but it took the help of artists to promote it.

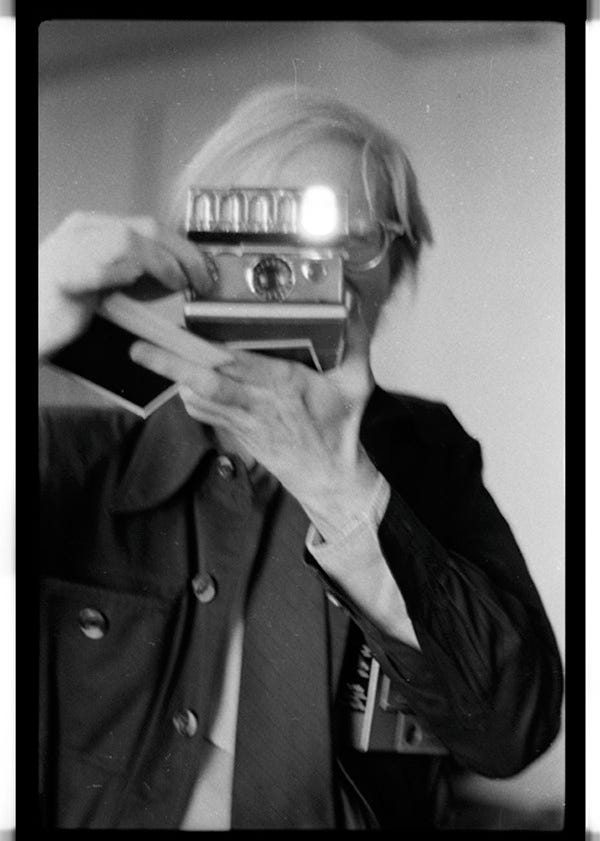

The 20th Century went from monochromatic stills, motion picture, and video into a Technicolor age, ushered in by artists using their imagination to experiment with the creations of scientists. In the 1960s, Land invited hundreds of artists to create with his Polaroid cameras. Andy Warhol was among those eight hundred artists who were invited to created art with it.

Polaroid became one of the leading companies of the 20th Century, and Land’s contributions were varied and far-ranging, including advanced technologies for national defense, such as the famed U-2 spy-plane, but he may be most remembered by most people for his artistic impact on society. And then one day it ended.

For Land, like Daguerre, Imagination and Creation, Art and Science, moved on again.

Many of Warhol’s Polaroid portraits were of actors who worked in Hollywood, thanks to Robert “Bob” Evans. Evans’ role in a movie was saved when a Hollywood power broker said, “The Kid Stays In The Picture”*. Evans was a “B-list” actor who became the driving force of Paramount Pictures, a subsidiary of Gulf + Western, creating films like Rosemary’s Baby, Chinatown, and The Godfather. Evans opened the doors to artists doing new kinds of movies at the studio.

One of the challenges facing people who want to test the limits of the Imagination and Creation include the “experts”, critics and power brokers. The stock-in-trade for these self-appointed classes is to decide who’s in the picture - but that’s ending slowly.

I think that the things we’re afraid of, will become, yet again, the tools that we will use in ways that give us more autonomy and agency, away from gatekeeper eyes.

We don’t need someone to say that we “stay in the picture” because the world has changed again in strange new ways, enabling the rise of personal republics of the imagination.

This is where this riff ratchets to a whole new level, from history into the speculative. I wear my science fiction hat, and imagine what this all means.

THERE IS ROOM FOR MORE, NOT LESS, IN A REPUBLIC OF IMAGINATION

In “Information Wants To Be Free”, by Cory Doctorow, there is an intro, by Neil Gaiman about a story from 1958 science fiction story.

Apologies for the quality of the image but I took a pic as soon as I got the book and read that forward. It struck true. I want to quote it again, bear with me:

“This morning, we had an economy of scarcity.

Tonight we have an economy of abundance.

This morning, we had a money economy— it was a money economy, even if credit was important. Tonight, it’s a credit economy, one hundred percent.

This morning,… selling standardization. Tonight, it’s diversity.

The whole framework of our society is flipped upside down.

And yet… It doesn’t seem to make much difference. It’s still the same old rat race.”

— from “Business as Usual, During Altercations,”

by Ralph Williams (Astounding Science Fiction, 1958)

Art has an imaginative power to raise questions which can only be solved when we “science” the heck* out of it, creating both beauty and knowledge.

This is the power of Art and Science’s dueling duet, to transform scarcity into abundance, to shift from the old standardization to the diversity of imagination and creation. But “It’s still the same old rat race” if we’re playing the same old game.

But what if the game has changed?

We have an abundance of words, to transform into pictures in an instant. We need help.

Deflation in technology has led to hyperinflation in content, media, noise, and made signal a luxury good. The machines are slaves fed on lots of noise and some signal.

I think of all of science’s works, transformed by art into memory, history, and story.

Mankind has accumulated, even with the erosion of time, a Mount Everest of imagery.

There are people who sell us images of the world through their gatekeeper eyes but we have eyes too. We’re part of the picture, we should stay in it, every one of us.

What I imagine ahead: the dropping cost to build personal private networks for our curiosity.

We have a moment before us, like the “Altair” computer circa 1976, kludgy but enough to tantalize geniuses to build, one to write software for it, ala Bill Gates, the other to make a machine of their own, ala Steve Jobs, opening the field for artists.

What is that “Altair” moment? Yes, here is the part about “Large Language Models”.

Another Evans, Benedict Evans, mused, “… in the 2000s suddenly anyone could find whatever images they wanted (or didn’t know they wanted), and now anyone will be able to make whatever images they can imagine, for better and worse.”

Think about the connecting thread between Camera Obscuras, Daguerreotypes, Polaroid, and ready made pre-mixed paint colors. The one thing they all have in common are increased spontaneity. The next new strange tools also offer spontaneity, freeing the artist in everyone.

There are chores these new tools can do, ala automation of repetitive tasks, while the higher level work is still up to us: the assignment of meaning and context.

For the moment, I see super-shape shifting stencils at scale, which need us.

We bring the goods because we bring the meaning, so we should focus on mindful work.

I think of “The New”, which is the name of Jeff Koons’ debut exhibit of twenty vacuum cleaners under glass. Koons’ imagination gave utilitarian objects with new meaning.

The prosaic and quotidian is transformed by the light of meaning.

The next new thing doesn’t do “meaning”, we do that that part.

My wish-list is our private hosting of instances of instrumentalities takes over mindless endless consumption. Let the machines doom-scroll so we can do other human things with our time, our imagination. This is a new kind of productivity inside.

My belief is that the storyteller, as artist, is at the heart of the mix.

These tools that many want to abolish will be used best of all by artists.

It comes down what Edwin H. Land knew about his creations, which was the same thing that Steven P. Jobs also knew, that the potential of their creations was best realized by the imagination of artists, artisans, and scientists.

Land and Jobs understood our imagination was our camera to create pictures of the future.

A camera of the mind is coming, and we will all become artists, and founders of our own republics of the imagination.

Our "cameras of the mind" are private readers and jungle guides on networks. Our private machines of mindfulness will keep us where only we can go, focused on meaning.

Last thoughts:

Everybody's a luxury category for somebody else in the world - there is plenty of room for art.

NOTES: I was captivated by Victor K. McIlheny’s biography of Land’s life, “Insisting On The Impossible”, and by Harvard University’s Baker Library Historical Collections. This riff is concluded.

Neat! I just wrote about Daguerre, looking to the past so I can understand the future better. I particularly love the junction of art and science (including art and technology), and I have the same questions about today's generative AI. I think it's a canvas with paint on it, a medium we need to understand we are moving around and allowing it to sort of create itself, the same way the medium is a part of the painting... but beyond that, it's going to be really, really interesting.

I felt a click as you went from DaVinci running out of paint to the "flashy" work of Monet being made possible by advances in pigments, tubes, and brushes. There is something fun about framing the history of art as mere economics of scale -- although I know we both know that's not what drives artists. You walked a line there in a fun way.

Also, I like how you hint at AI without needing to say it. Keeps the joint feeling classy. Who knows what the future holds for artists -- but it will likely be balked at by the purveyors of "real" art.

Thanks for the read, Rooster!