The Optickal Phantasies Of Utopia And Dystopia

The beginning rises and falls under the same sky

Welcome to an entry “From The Future”.

This is a riff-in-progress. What you are reading will not remain the same. It will change. It will be feed-stock for something unexpected - like all experience.

A “prompt” courtesy of the Soaring Twenties Social Club, a creative community: “E_ECTION”. I add a song from Queen, and Sir Isaac Newton for a long riff.

The word “Elect”, as in “election”, has Latin roots in “Ex” and “Ligere”, “Out” and “To Choose”, with deeper Indo-European roots in “Leg”, “gather, collect”. It also has roots in “Lecture”, as in “lectura”, “reading from”, and “a discourse”.

We gather for a reading about the choosing of Futures. It is an improvisation which began with a song and a centuries old science classic.

Future + Fiction is the formula for everything - an essay, story or chapter.

A Notebook Audio Discussion Version of the piece.

Many pieces are best read online, via Substack App, within fifteen minutes.

Is this the real life?

Is this just fantasy?

Caught in a landslide

No escape from reality

Open your eyes

Look up to the skies and see

-“Bohemian Rhapsody”, Queen

The beginning and end of everything rises and falls under the same sky. One person’s Apocalyptic trash is another’s Elysian treasure. Fears of missing out waltzes with a love of moving on. Welcome to the currency of every hope and fear about the future, marked utopia and dystopia, a coin of the mind.

You can try but you can’t avoid staring, at the feeds flowing past, the mood-scrolling of algorithmic fever-dreams, the models of abstractions, and the volatility of ad hoc “indicators” - of “that which can be measured (but was made up)”, in markets, market shares, shares, share of minds, mind-shares, and minds. It’s the end of the world. It’s the beginning of a new one. Again.

Utopia and dystopia are siblings, unreal realities, irrealis realis, of the future. Some are visions of “sufficiently advanced” Arthur C. Clarke magic, and others are bundles of fears about what could go wrong. And like siblings, despite their polar differences they share a common parentage - they reflect us. The truth is that they’re self-portraits of Man.

Our greatest minds, gazing skyward or looking inward, speculated in the reserve currencies of the mind, replacing old models with new ideas, transferring their visions to new systems of the world. They make an Age.

Enter Isaac Newton.

Isaac Newton had as unearthly a mind as there ever was but he was not a machine. His imagination lent themselves to life, money, and God just as his intelligence led him to rewrite ancient rules of light, motion, and gravity.

Here is my “lede” below. Imagine an 18th Century-style headline:

“The Optickal Phantasies of Utopia & Dystopia: inspired by Sir Isaac Newton, the useful Jeremy Bentham, the happy John Stuart Mills, & brilliant dark forests”

1666. The year when Isaac Newton, “conjured up calculus, light spectrometry, and the theory of gravity in a flurry of creative genius….”1

The year before was perhaps the real miracle year. 1665.

In 1665, Newton was confined to his rooms at his family home, Woolsthorpe Manor, with Cambridge closed down as the plague sprawled outside. He re-examined what he was taught at school, and turned it inside out.

Aristotle’s model of reality was the starting point for everyone at university, where the Earth was the center of the cosmos, with everything revolving around it, pushed along by a force of constant motion. Terra prima.

The old model was also where it ended for most students, who went about 1600s life. Isaac Newton was back home on the farm and had time to think.

A miracle year was possible because a change in philosophy preceded new principles, and it began with notes entitled, 'Quæstiones quædam Philosophiæ' ('Certain Philosophical Questions'):

“With the “Philosophical Questions” project, Newton ended any residual interest in Aristotelian doctrines and embraced the delights of the so-called new philosophy. Over the next three years (which included the annus mirabilis of 1666) he would make seminal contributions in optics, physics, and mathematics, although none of these achievements would seep out of the walls of the college until the end of the decade….” 2

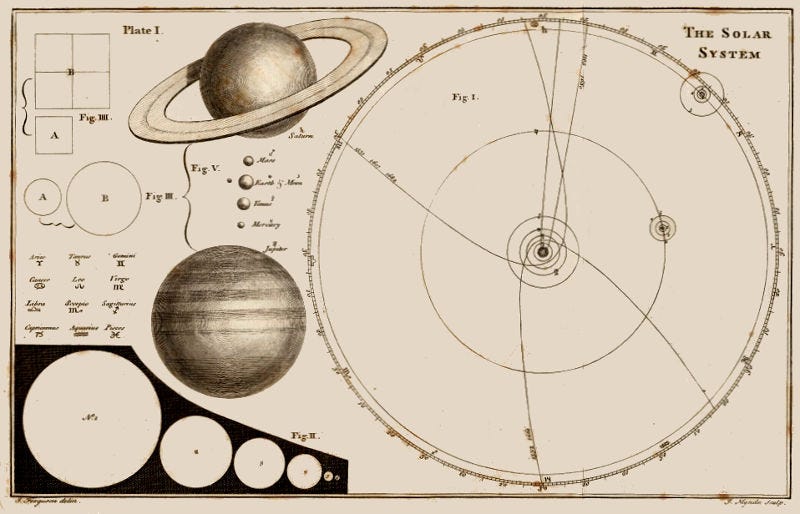

Newton’s vision of gravity, the planets, and the laws of motion, in his “Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica”, or “Principia”, were answers to his ‘Quæstiones’, twenty years in the making.

Questions asked in the 1660s were answered in the 1680s.

Newton would leave behind the dominant models of the heavens and laws of motion. Aristotelian observation gave way to Newtonian calculation.

He would stop Rene Descartes’ vortices, invisible whirling forces of motion, and would rearrange a geocentric model of the Solar System - where a stationary Earth was orbited by the Sun and planets - by determining that gravity existed as a universal force in each particle of matter. He would provide the bookend to Johannes Kepler’s three laws of planetary motion for a heliocentric model of the Solar System, with laws of motion for everything.

The force of Earth’s gravity countered the centripetal force of its motion, so much that it could indeed orbit the Sun while also spinning, with none of us aware beyond the sun’s rising and setting, and the very slow wheeling of the stars in the evening canopy. The Sun would be the “center” of the Solar System with the Earth relegated to mere planetary status, while their motion was described by three laws of motion, inertia, momentum, and reaction.

But that was in the future.

The plague over in 1667, Newton returned to Trinity College, but had not published a word of his work, not yet.

Newton’s Next Miracle After Principia

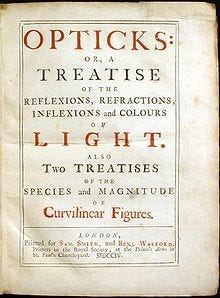

Newton’s other miracle was a study of light. Where Principia focused on motion, gravity, and the Earth, Opticks was a record of experiments about color, light, and the Sun, as first reported to The Royal Society of London in 1672. His embrace of “Mechanical Philosophy” during his college years led to Principia and then to a magisterial study of light.

From Flammarion, a 19th Century emulation of Medieval/Renaissance “woodcut” of a pilgrim breaking past the firmament of reality. Not Newton.

Opticks: or, A Treatise of the Reflexions, Refractions, Inflexions and Colours of Light, by Isaac Newton, published (first in English) in 1704, was one of the leading works at the dawn of modern science. Presented in vernacular English instead of the classical Latin of scholars (in which Principia was written), Opticks was written in a way we understand today, with metaphor.

Work which began in 1672, took a generation to come to light in 1704.

Atypical of Newton’s avoidance of “what ifs”, his study of refraction included a speculation that light was made of discrete “corpuscles”, evoking the “photons” of diffraction and 20th Century physics. It was that time confined to home, but freed by his imagination, when Newton began to displace 20 centuries of ancient and Aristotelian models, including one of light as divine transmissions.

Newton used prisms to break apart light into colors, and he made himself a part of many experiments, as he prodded at his eyes, and stared at the sun, to study the “spots” he saw when he shut his eyelids, to see pieces of light.

He both saw and imagined, objects of light with the “camera obscura” of his eyes. There were things seen, and there were things phantasized.

“All the Colours in the Universe which are made by Light,

and depend not on the power of imagination,

…

I speak here of Colours so far as they arise from Light.

For they appear sometimes by other causes,

as when by the power of phantasy we see Colours in a Dream,

or a mad Man sees things before him which are not there;

or when we see Fire by striking the Eye,

or see Colours like the Eye of a Peacock's Feather,

by pressing our Eyes in either corner whilst we look the other way.”

— The First Book of Opticks, PROP. VII. THEOR. V.:, Sir Isaac Newton

Within the four corners of notebooks and rooms, the inertia of ancient ideas was overcome. Where the “Colours in the Universe which are made by Light, and depend not on the power of imagination” is our starting point, we then see with far more than our eyes. Beyond Newton, our sight relies upon “phantasy”.

Our creative facility to fill in the blanks faces limits because there’s only so much “realis” that we can process. When we open our eyes, our brains fill in the blind-spots, surrounding what is a fuzzy incomplete upside down picture, of the camera obscuras of our eyes, hitting our nervous system.

Our brains do more with what we literally see. Reality trickles through at 17.5 mbps through our eyes, as our minds host a streaming show at 60 bps when we’re awake. For a rough scale, were our day to day reality about the size of New York City’s population, our minds are ‘bed and breakfasts’ able to host 4 families of 4 but much more is going on than that.

When we sleep, our minds unspool and spill out from the experiences of waking hours, to develop memories into dreams. It paints with much more than light. Our minds fill in the canvas with phantasies, including visions of the future.

Imagine a broad spectrum of visions of the future - Utopia and Dystopia - because the prisms within each of us are unique. No two ways of breaking apart the light of reality are alike, no two visions of paradise and perdition the same.

But, what is Utopia and dystopia? Where does the idea come from?

Let’s go back further in time, to a source, maybe THE source, before continuing.

More than a 120 years before Newton was born in 1643, when the cosmos was still described in Aristotelian terms, Sir Thomas More wrote “Utopia” in 1516.

Born in 1478, More was a brilliant scholar who was sent to Oxford, but was later forced to leave by his father to begin training for a career in the law and politics. In our history, in 1504 More entered Parliament and politics - in alternate reality he might have become a monk instead of later becoming King Henry VIII’s Chancellor. Loyal to his friends and beliefs, it was the latter which led to his downfall when he would not support the King’s marriage and succession plans. This devout scholar was executed in 1534.

More was also one of history’s first speculative writers, having written an imaginary work about the ideal political State. He wrote it in Latin, in 1516 and his close friend Erasmus got it published but it wasn’t until 1684, 150 years after More’s death, that a now widely known English translation was published - just a few years before Newton published his Principia with the help of Royal Society colleague Edmund Halley (of “Halley’s Comet”) in 1687.

More chose the name “Utopia” as a play on Greek words for “Good Place” and “No Place”. He looked at his times and created a wish list in story about a fictional land that represented the opposite of what he saw around him, a place with fewer but simpler laws and no lawyers, where everything happened in public view (and not in smoke filled backrooms), and there was no money and private property. Treating the work as a portrait, its he work of a brilliant man of principle in a world run by princes, of a frustrated Monk versus the political insider close to royal fires of the 1500s.

If Utopia and Dystopia , as I suggested, are self-portraits, then one of the first was a diptych, a piece work, that was part-still life and part-abstract. More’s perspective of 16th Century political economies and realities was cast in sharp relief against a fantastical vision and way of life of an imaginary island state of Utopia. The “self-portrait” analogy is appropriate given that Thomas More used a fictionalized version of himself talking with a fictional traveler, Raphael Hythloday who visited Utopia island, as criticism and aspiration.

In More’s Utopia, everybody is expected to work, with their contribution based on ability, while compensation was based on need, and not money based, for there was no money and no wealth to accumulate, no wealthy classes. In short, this was More’s critique of what he saw around him, greed.

We begin to see a tradition of creating a vision of The ideal island as a proposal for a “better world”, with the author hinting that the larger real world should be a larger scale version of an imagined idyll, an irrealis realis, an unreal reality.

Let’s rejoin Isaac Newton in 1670 (and 2060).

Isaac Newton’s Vision Of The Future

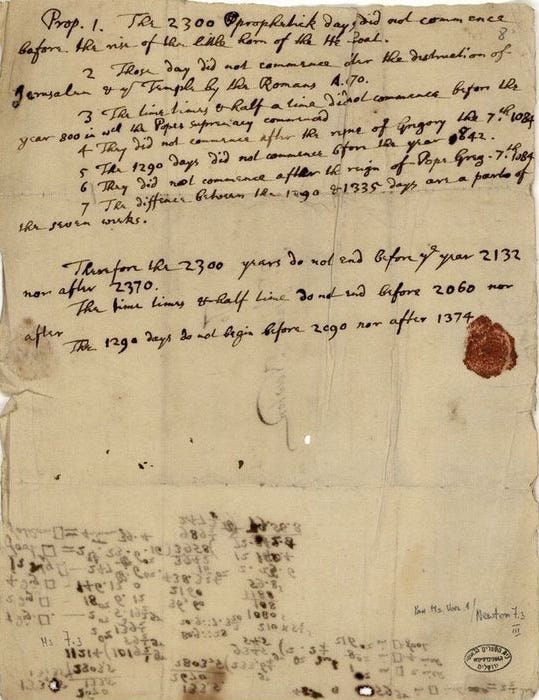

In the wake of his vita mirbilis, his miraculous life, Newton examined the biblical end of the world. The qualia was cast in quanta, a biblical chronology was written by a master of mechanical philosophy. He started in 1670, and studied the prophesies within the Old and New Testaments, which took on depth and detail in the last years of his life. According to a 1704 manuscript, Newton estimated the earliest possible year for the end of the world: 2060 CE

There would come plagues, warfare, and then 1,000 years of bliss - Newton envisioned, phantasized, then he would become one of its saints. The “End” was followed by a garden. The things to keep in mind for Newton’s spiritual “phantasies” was that they were drafted during the time’s religious and political strife between defenders of differing visions of faith.

Revolution and Revelation was front and center and Newton, already prominent for his miracles, was involved. About the same time that Newton was publishing Principia by 1687, he was also contesting political faith-based appointments under James II for Oxford’s Magdalen College. Newton was still a man of his times. He didn’t foresee the future so much as portray his present.

The new ideas which change models of the world, the future, and of reality, also hosts within the limitations of the latest model, the next “System of the World”.

We cannot see outside the four corners of our minds, for what we “see” as the beginning of an end might well be an end of a beginning, or vice-versa.

Our foresight of the future has blinders and blindspots, for we can not know, we can only believe, imagine, and speculate. We adopt new oaths based on an intimate faith in our ever-shifting feelings about the future. We genuflect to our hopes and fears, our envies and rivalries, our loves and hates, all from our times.

For all of the numerate power of Newton, he had a blind-spot. Money.

While Newton understood that “a mad Man sees things before him which are not there”, he missed an opportunity to apply this to another area of his life.

The same man who wrote Principia, Opticks, and imagineer of the world’s end, was blind-sighted by his own speculation. It came later in life, when he was more preoccupied with material and spiritual wants, on Boxing Day 1699, at the end of his true century, as the last appointee from within the Royal Mint.

As Master of the Royal Mint, Newton defended the coin of the realm, and was an active foe of counterfeiters and coin clippers, criminals who took bits of gold coins to steal gold without stealing the coin. He was adept at catching criminals but he could not avoid stealing from himself during an investment mania, despite having already made a profit early on in a market boom. Newton could not withstand the allure of a bubble which continued to inflate without him. The man who rewrote the laws of motion never discovered the love of moving on from a market mania.

Newton made money on the way up, and cashed out. He then had a fear of missing out as others stayed the course with rising profits, at least on paper. With a bit of mimetic desire, rivalry, envy, Newton re-invested just as the mania took hold with ruthless efficiency and delivered financial ruin.

The Master of the Royal Mint lost more money than he made in the market.

The man who restored England’s money supply by melting down all the old silver and coinage for a modernized “milled” coin for “the Great Recoinage” and doing real work as Master of the Mint for a record term of thirty years - in what was treated as a royal sinecure position - could not protect himself from his own monetary envy and desire. The man who restored trust in the Royal Mint, adjusted the currency standards for gold and silver coin, was swayed to trust one too many times in the passions of the South Sea Bubble.

We do the same in more than money. The dystopian ends of the world and a utopian paradise of new realities, are part one common phantasy - that we can say the future we imagine or fear is certain. We clip the edges of coins of the mind, to get one up on the future like thieves trying to outsmart reality.

We steal from ourselves the possibilities of seeing outside of the mania for the latest “current” realities on offer. We’re vulnerable, thanks to the feeling of missing out, while we chase in hopes for more of what was. But what was has moved along, and the future isn’t what we hoped (or feared) it would be.

Newton’s brilliance was not enough. He decried the madness of men and money, but he couldn’t confront the truth that he participated in that same madness, with a fear of missing out on a market mania.

There is a cautionary lesson here about competence and overconfidence, about what we think the future should be, because the world contains billions of visions, billions of seeds of things to come.

There’s a boldness in playing the future game, including for utopia and dystopia, but it is still a mirror of how we see ourselves. The boom and doom are both reimagined presents.

Can we be humble about our intimate madness, our fears and hopes, even if they’re somehow quantified, made precise, and take a true measure of ourselves before we set our yardsticks upon the world?

Think about everything that came before as we move on to the next new “after”.

Empty fields become empires, and back into empty fields, again and again, shelving and tantalizing with what might have been. We fill in the blanks with ambition and imagination to repeat the cycle, certain that this time we’ll get it right, and that this time is different. We’ll win the future for good.

Mankind has seen many great ancient empires all passed into history, and consumed by myth. Newton was familiar with many “Ends of the World” of many empires. In his posthumous “Chronology Of Ancient Kingdoms”, Newton wrote a historical timeline from ancient Greece to Alexander the Great, the names and places are legion. Utopia for victors, Dystopia for the conquered.

Beyond Newton’s work, there were many other names, also long past from memory to mythology, including by not limited to Ancient Athens, Babel, Babylon, Byzantium, Cahokia, Cuzco, Imperial Rome, Troy, Tyre, Uruk, and Xi’an. The sun rises and sets, again and again without end, each day, leaving behind a growing piles of utopian victories of what was and dystopian warnings of what can happen. More endings followed by more beginnings.

Despite our history and mythology, notice how we try again and again, and raise new monuments to test the fates and our faith in our imagination.

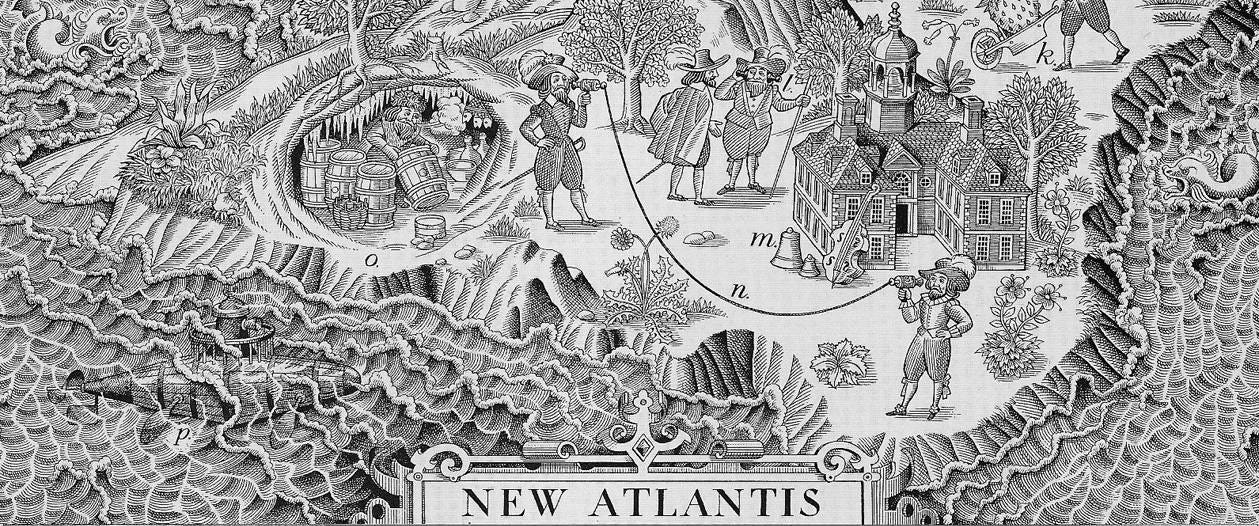

Francis Bacon charged the imagination as the offending source of idols which afflicted our sensibilities, even though he was likewise guilty by giving into his imagination by writing his Utopian novel “New Atlantis”. His unfinished story of a ship’s accidental landing on a Pacific island, home to an advanced society run on civility and the scientific humility of experimentation, was one of the inspirations for the Royal Society - a scenius of natural philosopher aristocrats, founded in 1660, which began with Bacon’s ideas and became more.

It was fitting that Bacon’s story about a Utopian society was unfinished, and paired within a post-humous 1627 compendium of his scientific and historical studies, “Sylva Sylvarum: or A Naturall Historie in Ten Centuries”. It matches the real world’s unending work. Even as one chapter of the world reaches its end, another begins (we hope), and history and the story goes on.

Bacon’s scientific rational society is born on an island called Bensalem, “Son of Peace”, which survives the end of a civilization’s militarism, greed, and corruption. A New Atlantis emerges, a utopian phoenix out of dystopian ashes.

If a story, like history, never truly “ends”, then the future remains in charge of deciding what’s next, and is free to change its mind.

If history is the exchange an older model of Utopia for a newer one, perhaps dystopia includes the trap of not moving on from the past. We struggle between our love of moving on to something new and our age-old fears of missing out on what was and hoping that for its return. We forget this because even as the meanings of everything human remains the same, new generations express them with new words.

Even as an empire fades back into empty fields, another already begins.

Years before the posthumous publication of “New Atlantis” by Bacon’s friends, from 1609 onward in his life, Bacon channeled his imagination and sensibilities towards the founding of real faraway places of the future, in the Americas, Virginia, the Carolinas and Newfoundland, which long outlived him.

Such was Bacon’s influence, that Thomas Jefferson, of Virginia and the third President of a nation forged from the former utopian hinterlands of the British Empire, credited Bacon, along with John Locke, as among three of the greatest men who ever lived, with the third being Isaac Newton.

BEYOND NEWTON - From Natural to Moral Philosophy

The Useful Jeremy Bentham and The Happy John Stuart Mills

So great was Newton that when he died in 1727, he was laid in state at Westminster Abbey. His legacy was not just his works but his methods, his mode of scientific inquiry as a natural philosopher. These sensibilities were adopted for ethics by moral philosophers. They took on the material underpinnings of utopia and dystopia, the physical details beyond phantasy.

There was one who aspired to be a Newton of Morals, to apply the rigor of the experimental and quantitative to the human condition.

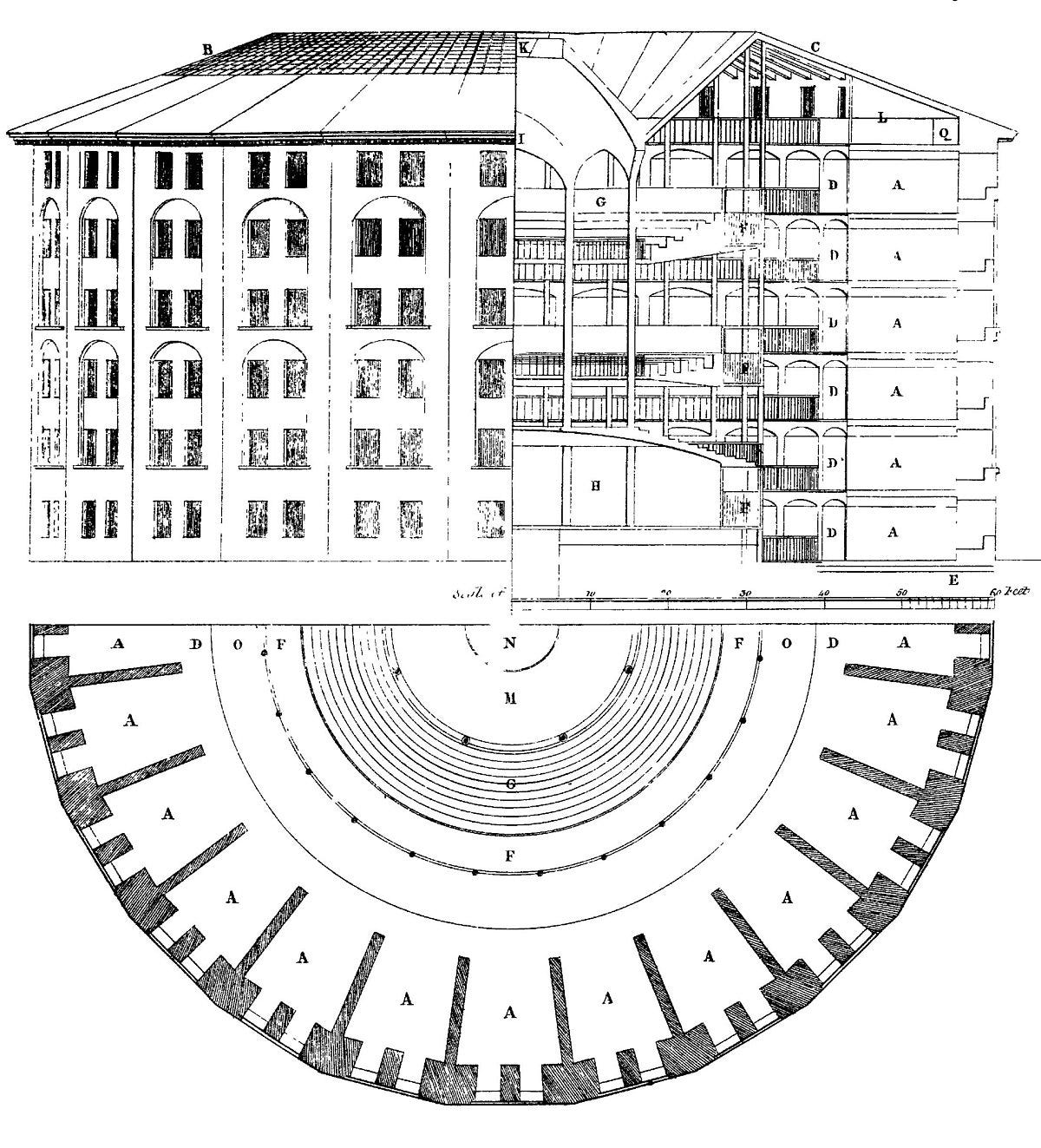

Jeremy Bentham, born in 1748, over 20 years after Newton’s passing, dreamed of a Pannomion, a rational utilitarian legal code, and suggested a moral ranking of everything we do or don’t do - a mathematics of hedonistic calculus. Bentham’s Utilitarian Utopia proposed “the greatest happiness of the greatest number” with as little pain and evil as necessary.

Bentham also imagined a “panopticon” as a shared space where everyone sees everything about each other. It was less a one-way experience in the modern understanding of it, and more an idealized space for optimization of the self by the many. This utopian conceptual physical space, however, stands today as a cautionary warning about dystopian consequences of enforcing one’s vision for the future on others.

Honesty was taken to one logical end point in the form of transparency, where everything was seen and known - the issue is when the State or mass entity executes an idea for its own ends.

Throughout history, whenever a society’s High Table delivers its version of “knowing everybody’s business for their own good”, a societal road-trip to utopia makes a hard turn off the road and straight into dystopian wilds.

The power to see all becomes a tariff collected by a Ferry-man. The coins minted have one side marked with a well-intentioned “optimization” of “In Happiness We Trust”, and the other an inescapable “Pay or Go to Jail”.

Bentham’s student, John Stuart Mill, born 1806, noted that conscience was still a motive for action or non-action, and was not to be discounted by any Utilitarian calculus. Getting to the greatest good were sentiments partitioned from the inner realities of each person, which forgets that real world “good” is made of many parts, including how we tick inside. We don’t optimize the human condition, it optimizes us.

Mill, however, despite his genius and the grand rolling scenius of geniuses which passed through his life since childhood, considered taking his own life, after admitting were he able to fulfill his desire and aim of a “just society”, he would still be unhappy. He saved himself not with quantities of maximal “good”, but with lines of Wordsworth.

“A medicine for my state of mind.” Words from Mill’s autobiography:

What made Wordsworth’s poems a medicine for my state of mind, was that they expressed, not mere outward beauty, but states of feeling, and of thought coloured by feeling, under the excitement of beauty.

They seemed to be the very culture of the feelings, which I was in quest of. In them I seemed to draw from a source of inward joy, of sympathetic and imaginative pleasure, which could be shared in by all human beings; which had no connexion with struggle or imperfection, but would be made richer by every improvement in the physical or social condition of mankind.

The qualia of beauty may feel more keen than any sum of the quanta of utility.

Poetry made life, and a life’s work, potent again for Mill. Let’s learn from him.

There’s an Ursula K. Le Guin story, “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas”, about prosperity for an entire society, and the price was that a child was brutalized. Even though it was fiction, it is a humbling reminder about the overconfidence we assign to our proposed futures because we are not omnipotent and omniscient, we cannot calculate the trade-offs, and even if we could, it’s “playing god”. In Le Guin’s story, an entire society’s paradise comes at the expense of a child’s endless brutal purgatory. We can become ugly gods if Mankind forgets being humane as well as human.

Looking back at Newton, Bacon, Bentham, and Mills reminds us that each and every version of “the future” has a cost. Utopia, Dystopia, Paradise, and Perdition are joined as part of one spectrum of unreal realities.

Hidden trade-offs come in every vision of the future, for each universal utopian phantasy a dystopian twin sits next to it, joined at the hip.

One size does not fit all, one vision of the future does not serve everyone.

UTOPIA DOES NOT SCALE

There was another Isaac who tackled the issues of a corrupt and decadent empire, long past its Utopian sell-by-date, fading into empty dystopian fields.

Enter Isaac Asimov and FOUNDATION.

Isaac Asimov, like More, Bacon, and Newton, wrote about a fictional “end of the world” for a galactic civilization bound into an empire in its last days.

One of his main characters, Hari Seldon, projected 30,000 years of barbarism before the birth of a new galactic civilization, calculated via Seldon’s psychohistory, a science fiction descendant of Newton’s Principia and earliest projected date for Armageddon, Bacon’s New Atlantis, and More’s Utopia. Seldon suggested that a Foundation could accelerate a rebirth in a 1,000 years.

Like all three gentlemen, Asimov was inspired by history for his story to consider the driving forces of the rise and fall of a large scale civilization. In their works we see dystopian paths to utopia, a corruption of the old, a fall from grace, and creation of the new, heralded by an island shining in the dark.

Like Bacon’s Bensalem in New Atlantis, a spiritual and scientific heir to Plato’s Atlantis, Asimov’s Foundation would carry on and start a new galactic civilization on the ashes of a fallen empire, hidden on the galactic empire’s capital world, Trantor, one world among millions, an island in a galactic sea.

WHICH WAY GALACTIC MAN?

WHAT IS THE NEXT BEST THING TO UTOPIA? NEWTOPIA.

We must create islands of beauty, while others strive to scale up someone else’s idea of Utopia for the latest empire of the moment - because people can’t help themselves - where the next best things to come are unique pocket paradises.

A PROPOSAL - A Payoff Inside A Tradeoff

Hidden Paradises: Burning Dark Forests and Light Ages Eclipsed

“An age is called Dark not because the light fails to shine, but because people refuse to see it.” -James A. Michener

I’ve heard of the phrase “Dark Forest” from science fiction writer Cixin Liu, author of “The Three Body Problem”, in the dystopian context of that a civilization must hide to protect itself from predation by other worlds.

The phrase “Three Body Problem” comes from a mathematics problem in classical physics - involving Newton’s universal gravitation and three laws of motion - where three bodies with mass, such as planets, orbit each other. There is NO one solution that ALWAYS solves it. Isaac Newton had tried to solve for it and could not.

The phrase “Hidden Forest” comes from physicist Enrico Fermi’s suggestion as to why we haven’t heard or seen signs of extraterrestrial civilizations: Everybody’s thriving in hidden spaces, safe from interference.

If we shrink this idea to a terrestrial scale, we recognize every experiment at building community and society faces tests of survival.

What survives is either too big, too small, or too “remote”. The big decays, the small is starved to death or swallowed up, while the “remote” has a chance.

History is filled with quests for a kind of beauty within boutique-size paradises. Pocket-sized societies, filled with the local flavors and brands of Newtopia, which are neither a world straddling Utopia nor a world-breaking Dystopia. Here, there are no empires to grow into empty fields ready for the next one.

A Newtopian future may rest in a constellation of many societies of the few, each like secret watering holes and private societies - where one size does not fit all but all will find a place bespoke for them.

Could it be that the real Dark Forests are luminous spaces, wherein their denizens reside on countless worldlets basking under the light of private suns?

On networks, they’re barely visible to our peripheral vision. Maybe we pass them by, while our short attention spans and memories erases their existence. We’re blinded to these invisible beautiful places perhaps by design.

Some people created private societies floating on networks.

People are building cities of the future.

Some are rewriting the laws and tax codes of tiny places.

Others, like Gerard K. O’Neill, suggested putting them in orbit.

They’re “New Atlantis” on spec.

They’re not everything for everyone, they’re slices of the future for some.

These idylls of irrealis realis are safe inside the interior of Dark Forests filled with beautiful places which “do not scale”.

In their secret depths, the bonfires to warm and light the way for those who know to feel their way in, visible only when looking for the right frequencies on a spectrum of realities.

We need the light which comes for half-lidded eyes, after night has passed - the ANTELUMINARY pre-dawn - when we can see just enough to search for and find the right “dark forests” within which are hidden illuminated paradises.

Utopia and dystopia leave blind spots for the other.

Tradeoffs exist and there is no weighting between them which does not exact a cost. Bentham’s minimum evil never gets a gimlet eye, and Mill’s conscience is a private affair. Newton grappled with gravity and light but not the human heart, greed, and avarice.

Utopia cuts off options. Dystopia cuts off optimism. Newtopia lets us choose.

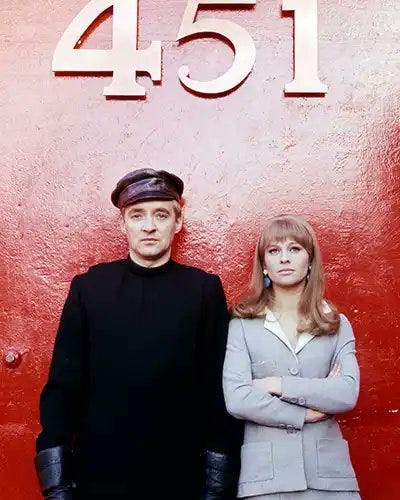

"I am a preventer of futures, not a predictor of them. I wrote Fahrenheit 451 to prevent book-burnings, not to induce that future into happening, or even to say that it was inevitable.” -Ray Bradbury

Sources Include:

'Quæstiones quædam Philosophiæ' ('Certain Philosophical Questions')

Chronology Of Ancient Kingdoms

Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica”, or “Principia”

Opticks: A Treatise of the Reflexions, Refractions, Inflexions and Colours of Light

Utopia by Thomas More

New Atlantis by Francis Bacon

John Stuart Mill Autobiography

“The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas”, by Ursula K. Le Guin

Priest of Nature: The Religious Worlds of Isaac Newton by Robert Iliffe

The Rigor of Angels: Borges, Heisenberg, Kant, and the Ultimate Nature of Reality by William Egginton

1

*Opticks: or, A Treatise of the Reflexions, Refractions, Inflexions and Colours of Light, by Isaac Newton

2

The Rigor of Angels: Borges, Heisenberg, Kant, and the Ultimate Nature of Reality by William Egginton

THIS WAS A LONG ONE. IF YOU REACHED ALL THE WAY HERE, THANK YOU

POST CREDIT SCENIUS

MY LUXURY DIS-BELIEFs ABOUT REALITY - SNEAKING FINAL THOUGHTS LONG AFTER EVERYONE ELSE STOPPED READING :)

We change focus, apertures, and exposure times to change images.

We do the same with our imagination. We “see” what’s “real”.

Light and dark are states of photons and perception. Imagery.

Utopia and Dystopia are states of mind and memory. Phantasy.

Our minds and memories supply plastic projection screens for unreal realities.

Each optickal “phantasy” is rendered within the cameras of our minds.

Thomas More resisted to Henry VIII, Isaac Newton resisted James II, each adherents to their faiths, men of principle of two different centuries, both possessed of such imaginative powers beyond their times. I scratch the surface of something miles, kilometers, astronomical units deep but I have one consolation, even if Utopia is best realized on an island, there’s more than just one. There’s an archipelago of idyll places, hidden but waiting for us.

If dystopia were truly that easy to realize, there would be no-one left, after centuries of warfare, famine, disease, horrors visited upon horrors. We are talented at destruction but we’re still here. Our stories are there to tantalize and terrify us into both non-action and action. The challenge lies in the choices.

The good news: Enough of us are talented at getting on with the task of surviving and thriving, the true utopia of all Man.

We’re still in charge of what to do with what we “see”.

Brilliant